Over the years, the Indian Subcontinent has seen many great empires, beginning with the Maurya Empire that covered over 5 million sq. km. of land! In this series of articles, we take a look at some of the greatest empires of the Indian Subcontinent.

The most powerful successors to the Mauryas, the Kushan Empire in North India (including Pakistan) and the Satavahana Empire in the Deccan, were both declining rapidly by 250 CE. They soon fragmented into a number of smaller states, which began scrambling among themselves for supremacy. However, before long, a new power arose that united and stabilized most of the subcontinent, leading to the Golden Age of Classical India- the Guptas!

Many historians consider the glorious reign of the Guptas as the pinnacle of Indian culture and civilization. Let us find out why!

4. The Gupta Empire (250 CE – 550 CE)

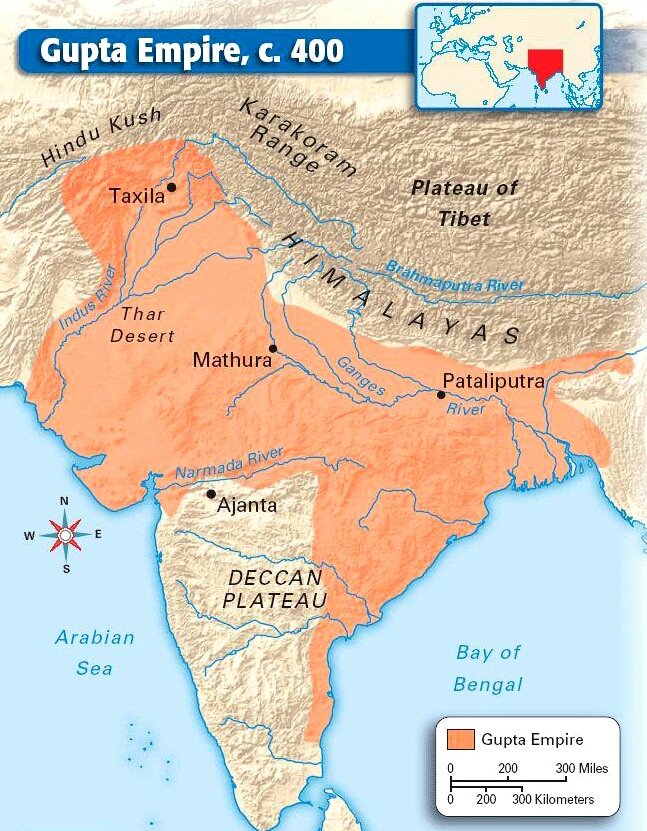

One of the most famous Indian Empires in history, the Gupta Empire rose in the 3rd century CE (AD) to cover 3.4 million sq. km. at its zenith. The Guptas originated in north India, most likely in present-day Uttar Pradesh, and were probably local warlords under the Kushan Empire. Belonging probably to the Vaishya class (or Kshatriya as per some sources) of Hindu society, they grew independent with the decline of the Kushans, and began carving out their own kingdom.

Rise

The empire began with Sri Gupta, a vassal of the heavily-declined Kushan Empire, assuming royal status in 240 CE. By 250 CE, he had succeeded in establishing his own rule from Pataliputra (modern-day Patna, Bihar) and stretching till Bengal. Assuming the title of Maharaja, he ruled till 280 CE. His son Ghatotkacha continued his father’s policy of cautious expansion, and arranged his son Chandragupta’s marriage with Princess Kumaradevi of the Lichhavis in 307 CE.

The resulting political alliance helped Ghatotkacha’s son Chandragupta I expand his influence upon coming to power in 320 CE. Over the next 30 years, Chandragupta I conquered the Magadha, Prayag, and Ayodhya regions. His empire now covering all of Bihar and parts of modern UP and Bengal, he adopted the title of Maharajadhiraj, meaning ‘King of Kings’ or ‘Emperor’. The gold coins minted during this period show both Chandragupta and Kumaradevi, denoting her substantial role in this expansion.

Zenith of the Empire

However, it was during the reign of their son Samudragupta the Great that the empire extended to become a sub-continental power. Coming to power in 335 CE, Samudragupta defeated 8 northern kings, conquering from the Himalayan foothills upto Malwa (modern Madhya Pradesh)! To the east, he defeated the Vangas to annex Bengal, and then conquered till Chhatisgarh, Orissa, and Andhra Pradesh. Several other rulers from Nepal, Assam, Uttarakhand, Karnataka, and Andhra became his tributaries, and the kings of Sri Lanka and South-east Asian countries sent lavish tributes in friendly alliance. He is often called the ‘Napoleon of India’, although, as he lived 1500 years before Napoleon and unlike Napoleon, never lost a battle, it should be the other way round!

To commemorate his victory, he performed the Vedic Ashwamedh yajna, signifying his supreme status as ‘Chakravarti’. Along with his extraordinary military career, he promoted arts and sciences and was an accomplished poet and ‘veena’ player!

In 375 CE, after a failed rule by his son Ramagupta, Samudragupta’s favored son Chandragupta II ascended the throne. He took the empire to the height of its power. Chandragupta’s daughter Prabhavati married into the Vakataka dynasty of the Deccan. With their support he destroyed the Indo-Scythian Shakas of western India to conquer up to the Indus River (modern Pakistan). He also carried out successful campaigns till Kabul, Afghanistan, noted via inscriptions of ‘King Chandra’. In the south, his influence extended up to Karnataka and Telangana through matrimonial alliances with the Vakatakas and Kadambas.

The Golden Age of the Gupta Empire

Chandragupta II ruled for 40 years, and established peace and prosperity across India. Known by the exalted titles ‘Vikramaditya’ and ‘Apratirathi’ (one who has no equal), his influence reached till Iran and South-east Asia. He promoted arts, science, literature, and philosophy, and his court became famous for the ‘Nine Jewels’ or ‘Navaratnas’- celebrated scholars from these fields.

Chandragupta II was followed by his son Kumaragupta I (415-455 CE), who maintained peace and continued the Golden Age. However, around 450 CE the Central Asian Hunas (Hephthalite or Hun tribes) invaded up to the Indus River, and the Prince Skandagupta defeated them. From 455 to 467, Skandagupta ruled in relative peace as well, barring small conflicts with the Vakatakas.

Decline

Skandagupta, the last of the ‘Great Guptas’, was succeded by his half-brother who ruled only for 7 years; and his son who ruled for merely 3 years. During the reign of Budhagupta (476-495 CE), the Huns repeatedly invaded and settled the fertile Punjab plains, greatly weakening the Gupta Empire, and requiring an alliance of Indian kings to repel them. In the time of Narasimhagupta (495-530 CE), the Hun ruler Mihirakula made devastating raids into Gupta territory, extracting tributes. Yashodharman, the King of Malwa, united with Narasimhagupta to completely defeat the Huns at the Battle of Sondani.

Rapidly declining due to devastating raids and administrative incompetence, the Gupta Empire ended in 550 CE with Emperor Vishnugupta’s death.

Political, Military, and Administrative Aspects

The Gupta Empire was a well-administered monarchy with a hierarchy of administrative divisions. The Empire or Rashtra was divided into 26 provinces called Pradeshas ruled by provincial rulers often called Maharajas. These provinces were further divided into Vishayas, each ruled by a Vishayapati with the help of a council of representatives.

The Guptas structured their military similar to the Kushans, along with some technological and tactical innovations such as siege engines and heavy cavalry archers. The army comprised of 4 main units: infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots. Interestingly, based on these units, the strategy game of chaturanga or Chess developed during this era, with the 4 units represented by pawns, knights, rooks, and bishops respectively! The Guptas also had an efficient navy protecting their vast coastline.

Social, Cultural, and Economic Aspects

The Chinese traveler Fa Xian during the time of Chandragupta II wrote that the country was prosperous and peaceful; the urban people cultured and educated, and the government was efficient. Crime was low, and punishments lenient.

The Guptas had trade relations with Rome, China, Persia, and South-east Asia. They exported luxury products like silk, fur, iron products, ivory, pearls to Europe and Central Asia. However, in later years, the destructive Huna invasions disrupted this trade and the accompanying tax revenues.

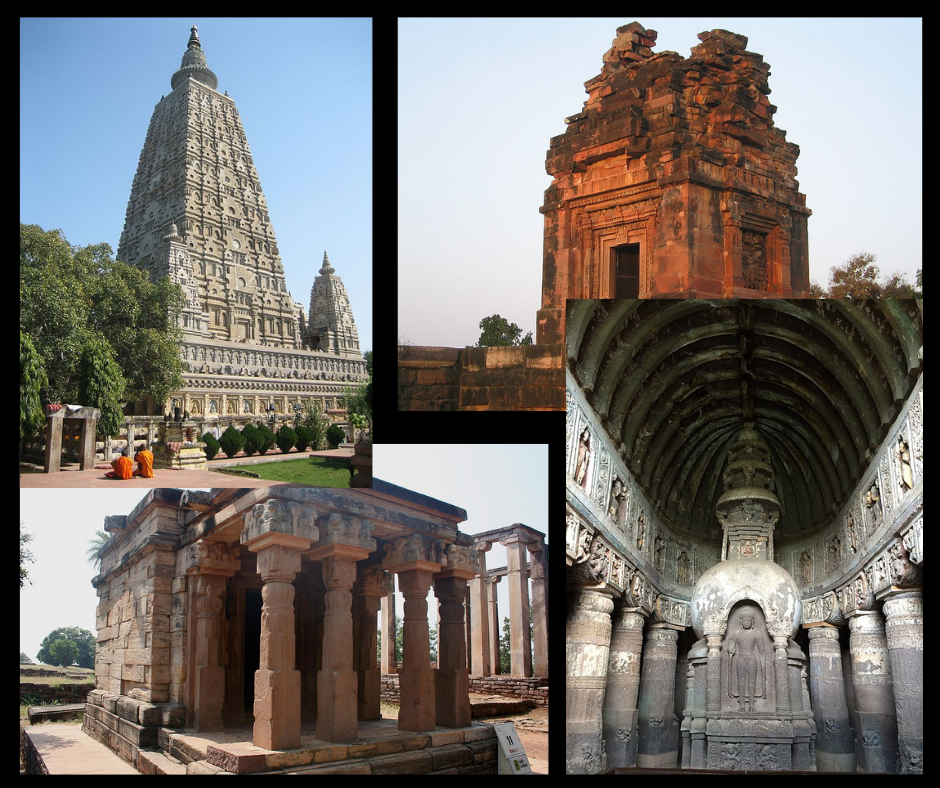

The Guptas were devout Vaishnava-sect Hindus, and also promoted other sects and religions like Shaivism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Kumaragupta I founded the famous Nalanda University, which became a global center for Buddhist and advanced philosophical studies. While society followed the caste system during this time, it was quite fluid in terms of occupation. The Gupta Emperors, most likely Vaishyas, intermarried with the Kshatriya Lichhavis and the Brahmin Vakatakas without obstacles or disapproval. However, Fa Xian notes that a few castes were considered untouchable because they indulged in hunting, fishing, or tanning professions.

The Guptas were renowned across the world for their patronage of literature, science, mathematics, and art. In fact, their encouragement contributed to the greatest surge in all fields ever seen in India, leading to the Golden Age.

The Gupta Empire– The Golden Age of Classical Hindu India

Literature: Among the Navaratnas of Chandragupta II, Kalidasa is recognized as one of the greatest playwrights and poets in the world, who took Sanskrit literature to its peak with works like ‘Meghdoot’, ‘Raghuvamsha’, ‘Shakuntala’, ‘Kumarasambhav’ and many more. Based on the Vedas, Puranas, Ramayana, and Mahabharata, his works have become extremely influential in history.

Another of the Navaratnas, Amarasimha, was a poet and a Sanskrit grammarian, who wrote the treatise Amarakosha containing a lexicon of 10,000 Sanskrit words. The famous poet Bharavi also probably rose to fame in the later Gupta era.

The philosopher Vatsyayana also wrote the famous Kama Sutra, a treatise on the pursuit of pleasure, and sexual and emotional fulfillment in life during this period.

Medicine: the Navratna Dhanvantari authored a medical glossary. The Sushruta Samhita, one of the oldest medical and surgical books in the world, was completed in its final form during the Gupta Era. It contains surgical techniques for probing, extraction of foreign bodies, cauterization, tooth extraction, caesarian section, fracture management, cataract surgery, and fitting of prosthetics.

Science and Mathematics: In this era, Aryabhata became the most famous Indian mathematician, astronomer, and physicist. In his mathematical treatise ‘Aryabhatiya’ he:

- Became the first to extensively use the place value system and consider ‘0’ a separate number

- Laid the foundation of Trigonometry by defining the values of ‘jya’ (sine) and ‘kojya’ (cosine)

- Became the first to propose the value of ‘Pi’ accurately to 3 decimals

In his work ‘Arya-Siddhanta’ on astronomy, he proposed some path-breaking discoveries:

- The earth is round and revolves around its own axis

- The movement of planets and stars observed is relative to the earth’s motion, thus providing the Laws of Relative Motion

- The moon and planets reflect the light of the Sun

- The earth and moon’s shadows cause eclipses, not ‘Rahu’ and ‘Ketu’

In the later Gupta era, Varahamihira wrote the famed Brihatsamhita which contributed to architecture, planetary motions, astrology, agriculture, mathematics etc.

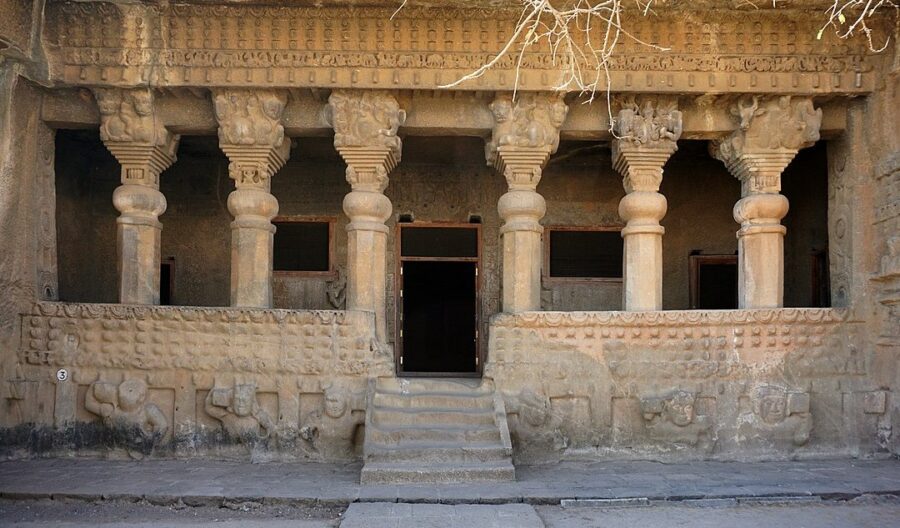

Architecture: We can see several examples of Gupta architecture among the various temples, stupas, inscription pillars and other structures. The Iron Pillar of Delhi, built by Chandragupta II Vikramaditya to record his victories and honor Lord Vishnu, has remained rust-resistant to this day, giving proof of the advanced metallurgical techniques of the era.

But when the Gupta Empire fell, the ensuing chaos resulted in the caste system becoming very rigid, caste intermarriage becoming rare, and a new social order of ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ castes emerging. India became fragmented again into small kingdoms fighting each other, and scientific progress declined. Thus, historians consider the fall of the Gupta Empire as the end of Classical Hindu India.

Legacy

The Gupta Empire marks the pinnacle of classical Indian civilization, primarily Hindu but also Buddhist and Jain cultures. The peace they brought to the Indian Subcontinent resulted in widespread prosperity, low crime rate, extraordinary scientific and artistic advancements.

Today, the Aryabhatta Knowledge University (AKU), Patna for technical, medical, management, and allied professional education, and the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Obseervational Sciences (ARIES), Nainital for astronomy and astrophysics honor the genius mathematician. The scientific and artistic achievements of this era influence the world, which has adopted the Indian numeric system and the use of ‘Zero. Kalidasa’s plays now translated in Persian, Arabic, German, and other European languages. And, we remember Samudragupta the Great and Chandragupta II Vikramaditya as two of the greatest emperors the world has ever seen.

All good things must come to an end, indeed; but they must never be forgotten. The Gupta Empire thus remains a fondly and proudly remembered golden chapter in the history of the Indian Subcontinent.